Judith Barry

News

Judith Barry in ARTFORUM

December 2018

Kathe Burkhart on Judith Barry The Artists' Artists: Judith Barry (Mary Boone Gallery, New York) in ARTFORUM.

Barry’s “… Cairo stories,” 2003–2011, rests somewhere between documentary and drama. Since her interviewees felt freer speaking anonymously, their texts about life, love, work, and the Arab Spring were transcribed and translated. In the resulting works, which were nine years in the making, she problematizes testimony from the standard-issue talking head by its delivery through actresses. In her video installation, fifteen women fade in and out of velvety black backgrounds in four groups of vertical monitors paired with still photographs. As in a game of musical chairs, viewers had to constantly shift position to see them all. Embodying collective experience with an intersectional twist that opens doorways to our shared humanity, the work reminded me that the personal is still political and the self is but a mask.

Judith Barry on HYPERALLERGIC

25 October 2018

Article by Deena ElGenaidi A Window Into the Lives of Women Living in Cairo on HYPERALLERGIC.COM.

At the Fifth Avenue location of Mary Boone Gallery, an exhibition titled Judith Barry: Cairo Stories attempts to chronicle the lives of women in Cairo during this period of social and political change. Artist and writer Judith Barry interviewed a diverse array of women in Cairo from the start of the United States invasion of Iraq in 2003 through the beginning of the Egyptian Revolution in 2011. Cairo Stories compiles those interviews into 11 diptychs — photography and accompanied text — and four plasma-screen videos. [...]

The videos included women from all walks of life, discussing a number of issues, personal and political, across the city of Cairo. One woman talks about street harassment and how years ago, her mother had hired a group of three women to yell at the men who harassed her. Now, though, she says things are different. Now, they have HarassMap, an app that tells women throughout Egypt which streets to avoid, but the woman in front of the camera laments that this isn’t enough. She doesn’t want to have to actively avoid certain streets, and she wishes the government would use the data in the app to make efforts to stop harassment altogether.

Unlike the diptychs, the stories in the video installations felt complete. Something about seeing the women and hearing them speak created a stronger, more well-rounded, concise picture of their lives and the lives of Cairo women. Through the video installations, Barry thrusts the viewers into these women’s lives. Listening to them speak gives one the sense of actually being in the room with them and pulls us into their deeply personal stories in order to build empathy and understanding.

Judith Barry in Boston Art Review

25 April 2018

Interview with Jameson Johnson Art In a Digital Landscape: In Conversation with Judith Barry in BOSTON ART REVIEW.

If you have visited the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston’s Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today, you would be remiss to have missed Judith Barry’s Imagination, Dead Imagine (1991). The installation is situated as the centerpiece within the “Hybrid Bodies” section of the exhibition. Showing five perspectives of an androgynous, human head on five respective sides of a cube (the top of the cube unavailable for direct viewing). Unidentifiable, thick, oozing liquids cover the head, then are wiped clean, leaving the head prepared for yet another cycle of subjugation. At 10 feet high, viewers are faced with an uncanny depiction of what could, or already might be, our abject reality. Yet beyond the contemporary and future implications of this piece, Imagination, Dead Imagine exists within a critical canon of uniquely disruptive, feminist art practice.

Barry’s work and career is nearly impossible to pin down to a single medium, discipline, or practice. Whether through writing, film, installation, or immersion, Barry utilizes a research-based methodology that places the viewer in direct conversation with the piece, thus providing subjectivity and multiplicity to the viewing experience. At a MIT Catalyst Conversation in March of 2018, Barry joked with the audience about the versatility of her work, stating that people are often “surprised” to learn a certain piece was created by her. As the audience laughed and nodded, I was struck by the validity and power of that comment.

Barry currently has two pieces on view in Boston: Imagination, Dead Imagine at the ICA and Untitled: (Global Displacement: nearly 1 in 100 people worldwide are displaced from their homes) (2018). Frequently traveling between New York City and Cambridge, Barry and I planned to meet at her MIT office, but were stopped by a late season blizzard. We corresponded via phone and email, exchanging thoughts and images about the two pieces currently on view while addressing the great expanses in between...

Judith Barry at the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston

7 February to 20 May 2018

Included in group exhibition Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, Massachusetts.

Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today examines how the Internet has radically changed the field of art, especially in its production, distribution, and reception. The exhibition comprises a broad range of works across a variety of mediums—including painting, performance, photography, sculpture, video, and web-based projects—that all investigate the extensive effects of the Internet on artistic practice and contemporary culture. Themes explored in the exhibition include emergent ideas of the body and notions of human enhancement; the Internet as a site of both surveillance and resistance; the circulation and control of images and information; possibilities for new subjectivities, communities, and virtual worlds; and new economies of visibility initiated by social media...

Judith Barry in the Boston Globe

26 January 2018

Article by Cate McQuaid A multimedia artist attuned to the zeitgeist in The Boston Globe.

When Judith Barry was invited to make a new mural for the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s façade, one image haunted her: a photo of people in an inflatable boat, shot from a drone.

“They were escaping from northern Africa,” says Barry. “I was intrigued by their hopeful expressions as they looked up at this drone. They’re in the middle of the ocean, trying to escape. It’s terrifying. But for this brief moment. . . .”

The mural, “Untitled: (Global displacement: nearly 1 in 100 people worldwide are displaced from their homes),” featuring a digital collage of a similar scene, is on view through June.

The multimedia artist, a professor at MIT, has two works in the citywide “Art + Tech” programming this winter. In addition to the Gardner mural, her 1991 piece “Imagination, dead imagine” is in “Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today” at the Institute of Contemporary Art.

The ICA’s chief curator Eva Respini says she considers the piece “an anchor of the show.”

“Judith is a prescient thinker, working on a cutting edge with digital and video technology,” says Respini.

Barry made “Imagination, dead imagine” at the height of the AIDS crisis, responding to the era’s terror of bodily fluids. She borrows the title from a Samuel Beckett story about people trapped inside a small space, and takes a cue from Beckett’s searing existentialism. In video projections on each face of a 10-foot cube, muck pours over people’s heads. Then the magic of video wipes the heads clean...

Judith Barry at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

17 January to 26 June 2018

Installation on the Anne H. Fitzpatrick Façade of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts.

For her installation on the Museum façade, American-born artist Judith Barry has chosen to work with some of the hundreds of drone images depicting refugees fleeing their homes and seeking a new life elsewhere. By orienting one of these boats vertically and populating it with the upward turned faces taken from these photographs, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Façade can act as a beacon: the faces forming a procession, illuminating the sky.

This work is presented as part of a citywide partnership of arts and educational institutions recognizing the role greater Boston has played in the history and development of technology. The Institute of Contemporary Art/ Boston has initiated this partnership to link concurrent exhibitions and programs related to the themes of the exhibition Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, on view at the ICA from February 7 to May 20.

Judith Barry in The Architect's Newspaper

7 July 2017

Review by Susan Morris Judith Barry's "Imagination, Dead Imagine" references horror films and J.G. Ballard in The Architect's Newspaper.

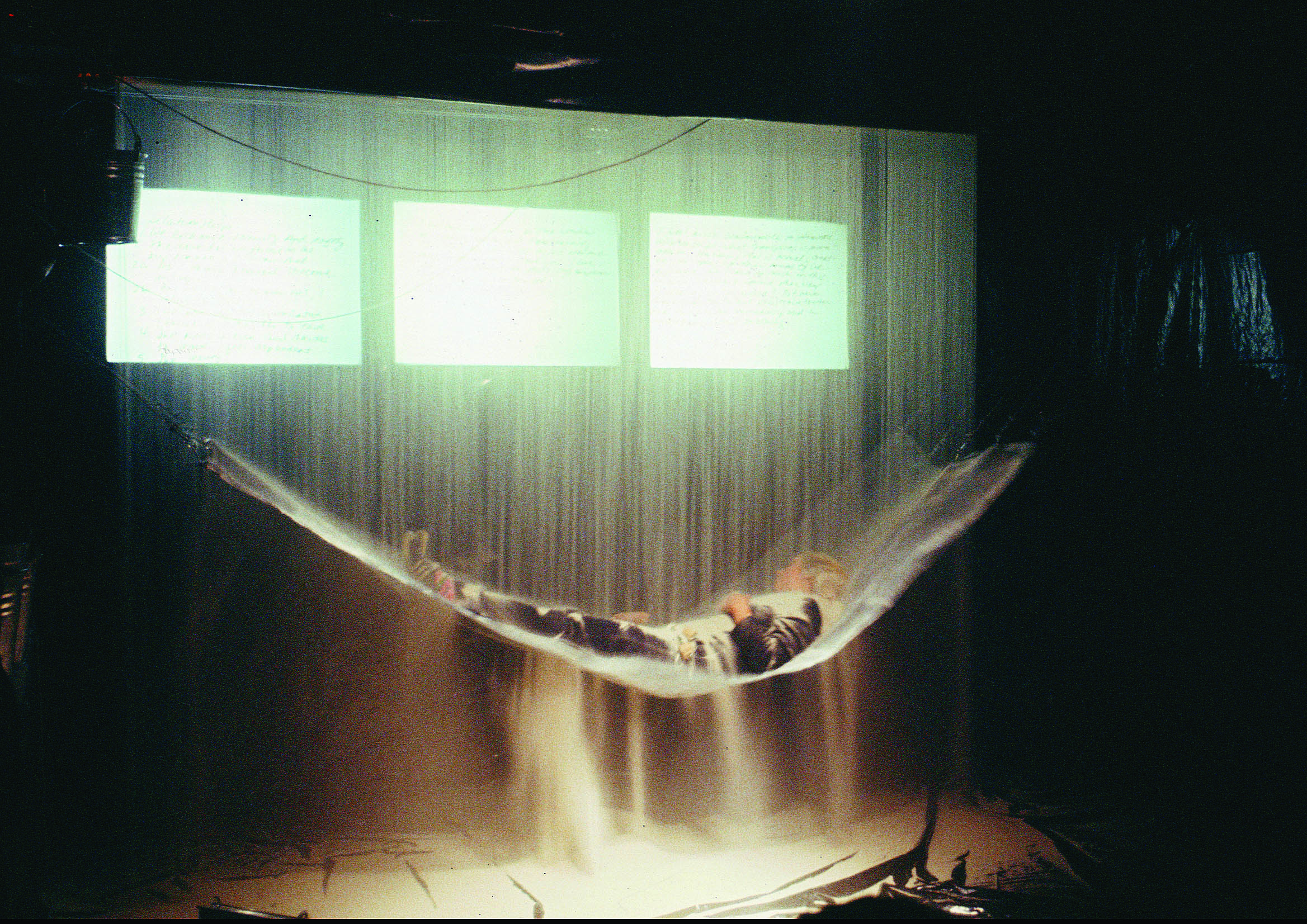

You enter a dark room illuminated only by a 10-foot-high rectangular cube comprised of four green-framed video monitors showing a face in close-up from all sides—facing forward, back of head, and both sides featuring the right and left ears (a 5th view could be seen from above, showing the top of the head), all above a mirrored surface where your reflected legs continue the bodyline. An androgynous, blue-eyed Caucasian with very regular features, bowed lips, and dark short hair has gelatinous liquid in a succession of yellow, red, brown, milky clear, and red-turning-to-greenish-yellow with small bits of debris, all simulating bodily fluids, poured onto it from above in a wash. A crinkly digital line clears the frame between each pour. At various points, crickets crawl and eat liquid off the face. Flaky white oats are sprinkled. Worms crawl and tumble down the face. There’s a flour snowstorm. Then the footage goes in reverses and the debris flows up. Throughout, we hear breathing sounds...

Judith Barry on FRIEZE.COM

20 June 2017

Review by David Geers on FRIEZE.COM.

Given the figure’s recent return in painting, it’s striking how little mention has been made of its appearance (and decomposition) in abject art of the 1990s. The omission may be purposeful: why dwell on the body’s oozy corporeality when smartphone screens offer confectionary distractions from the abject body in daily news – from tragic images of drowned refugees, victims of war, terrorism, gun violence and police brutality? Then again, perhaps this makes reexamining the abject all the more urgent today.

Consider Judith Barry’s imagination: dead imagine (1991/2017), named after Samuel Beckett’s last and shortest novel. Re-installed at Mary Boone, the massive, minimalist cube confronts the viewer with four views of a large head, projected atop its mirrored base. The face of this nameless, androgynous protagonist – a digital composite of a male and a female actor – remains impassive despite successive defilements, dispensed by some off-screen agent until an animated video wipe washes it clean and the process begins anew...